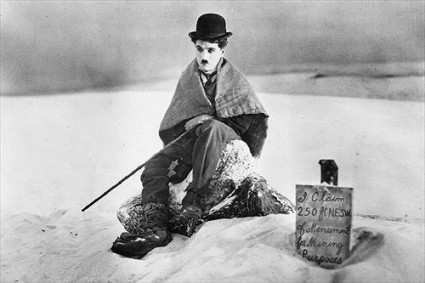

Gary Lucas playing to Dracula at the New York Film Festival, September 2010, with Carlos Villarias was Dracula, from http://www.garylucas.com

Will silent films survive? After the present generation of enthusiasts is gone, and now with almost no one left who remembers silent films the first time round, what impetus will there be in an age of HD, 3D, video games, home cinema, web video and mobile video to attract young audience to a silent, monochrome world filled with quaint manners, outdated narrative conventions and names that no longer hold the magic that once they had?

This issue was debated recently on the silent film discussion forum Nitrateville, and many interesting arguments were given for the survival of silent films. The great availability of silent films on DVD and Blu-Ray, the rude health (general global economic downturn notwithstanding) of some excellent festivals, the sheer fascination of viewing a past that recedes ever further away from us, scholarly investigation, the importance of book publications to inspire and intrigue, and the dedication of archives, all are cited as reasons for optimism.

I would add another, which is the silent film’s need for music. What is distinctive about the silent film as a medium is that it requires accompaniment by us. We have to add something of ourselves – our music, that is – to bring the films back to life. This performance imperative is not unique to silent films. Of course it applies to dramas, operas, indeed the music of the past. The playscript and the sheet music are the preserve of the expert until what they contain is given life through performance, is popularised. But what particularly distinguishes the silent film is that marrying of two forms of artistic expression – the film, and our music alongside it.

The Battle of the Ancre and the Advance of the Tanks (1917)

I experienced three illustrations of this last Sunday. It is surely strong evidence of the vitality of the medium that I was able to go to three very different screenings of silent films where the music was the real subject of interest in one city (London) on one day. I started off at Imperial War Museum to see The Battle of the Ancre and the Advance of the Tanks (1917). This documentary feature was made by the British goverment’s War Office Cinematograph Committee as the successor to the hugely successful The Battle of the Somme (1916), and the film – made by Geoffrey Malins, J.B. McDowell and Oscar Bovill – documents the later stages of the Somme conflict. While the film does not have the shock value or socio-historical resonances of the first film, it is more elegantly crafted and has shots of striking visual quality, in particular shellfire at night and iconic silhouetted figures against the sky.

The film depicts the routine of war in distinctively poetic terms. No other documentary medium can tell us so much about such engrossingly mundane details as soldiers donning thigh boots to fight off frost-bite, the wounded being given tea and sandwiches, and the ominpresent mud. It also features genuine footage (filmed at a distance with shaky camera) of troops going over the top and crossing no-man’s land. And of course it has tanks, which is what the public particularly came to see and which helped make the film a commercial success.

For the screening Toby Haggith of the IWM and pianist Stephen Horne had constructed the original ‘score’. As with their earlier project of The Battle of the Somme, there wasn’t a score as such, but rather a collection of musical suggestions for the different stages of the film, recommended in 1917 by musical director J. Morton Hutcheson. Horne has put together this pot pourri of popular tunes from the era, which was played by Horne himself (piano, flute and accordion), Geoffrey Lawrence (cornet), Sophie Langdon (violin) and Martin Pyne (percussion). The emphasis was on popular. Hutcheson had picked the pop hits of the day without much thought on their relevance to the film sequences they were to match, except for some association of names, though it was hard to fathom why a tune entitled ‘The Happy Frog’ had been chosen for a scene with a tank. As the film progressed so Hutcheson became more caught in the gravity of what was being shown and the music became of greater moment, but my abiding memory of the screening is of a line of howitzers shown to the sounds of a palm court orchestra with the occasional polite thud of the drum each time of of the guns fired. You did wonder what audiences made of such a musical mélange. Did it seem appropriate? Did it affect their view on what was on the screen? Did they hear differently to ourselves? Did they simply not pay it much attention?

This might seem to be the converse of adding our music to their films, but it is our modern taste to seek out authenticity in this way. Horne’s meticulous musical reconstruction took us that much closer to the past, while at the same time making the past seem all the more like the foreign country where things are done differently.

The brides of Dracula from the Spanish version of Dracula (1931), from http://www.garylucas.com

A few hours latter, and I was at the Queen Elizabeth Hall on the South Bank for two film screenings with live music that were part of the London Jazz Festival. This was something of a personal thrill as two of my favourite musicians were on the same bill. First up was guitarist Gary Lucas playing guitar to the Spanish version of Dracula (1931). This is the version of Tod Browning’s film that was shot on the same sets at night with a Spanish cast and director Geoge Melford. So yes it’s a sound film, albeit one with long stretches of silence and no background music except at the beginning and end. So why accompanying it with live music?

The effect certainly was jarring to begin with. Dialogue, translated titles and great swooping washes of electric guitar laden with effects pedals was a bit too much for the ears to take in all at once, but gradually you acommodated yourself to it, and Lucas’ wall of sound has proven itself an effective form of providing musical accompaniment to silents (notably his music for Der Golem) and now quasi-silents. He speaks through his guitar and his music is an expression of his enthusiasm for what is being shown on the screen. That’s the key point. It is not simply a rock musician doing his thing with a silent film (as others have done, often with painfully inapposite results). Enthusiasm for the film comes first, and with that an expression of that enthusiasm through his medium of choice – the electric guitar (two in fact). The result leaves the film still very much a 1931 film, but also one that connects through music with 2010.

The film itself is quaint, but while I wouldn’t say it was hugely superior to Browning’s original (as some have done), it shows invention and the sort of creepiness, except where adherence to the stage production drags it down. Carlos Villarias’s smiling Dracula drew laughter from the audience (I found him off-puttingly similar to Steve Carrell), but Pablo Alvarez Rubio (Renfield) played insanity as well as I’ve ever seen it done, and Lupita Tovar (Eva) was strikingly voluptuous.

Keystone, from http://www.davedouglas.com

The second film that evening was a silent film of sorts – a new work by experimental filmmaker Bill Morrison, who has enjoyed much acclaim for his work Decasia, composed out of found, distressed footage, which finds an otherworldly beauty in images in the process of decay. Morrison has continued to produced work in a similar vien, his latest effort being Spark of Being, inspired by the Frankenstein story, which he has developed with jazz trumpeter Dave Douglas. Douglas is building up a distinctive track record of silent film-inspired work with his band Keystone, though his modern jazz sound with strong beats behind it is better viewed as being inspired by the silents of Keaton and Arbuckle (subjects of earlier Keystone recordings) than ideal accompaniments to the films themselves.

The band came on stage – trumpet, saxophone, bass, drums, Rhodes and someone off-stage providing electronic noises – and played a punchy overture, then the film began. It was divided up into chapters (“The Captain’s Story”, “The Doctor’s Creation”, “The Creature Confronts His Creator” etc.) with the band accompanying what was shown on the screen. Morrison’s film is a mixture of distressed actuality footage and archive film, all of it silnet (or rather sound-less) including polar exploration (some of it Frank Hurley’s film of the Shackleton expedition), crowds (an amusing short sequence where people glower at the camera to signify public reaction to the Creature), two naked lovers running through woodland (““Observations of Romantic Love”) and a delightful sequence showing a Bavarian wedding projected at a slow speed that gave it a mesmeric quality). However, with the exception of the wedding, the archive film didn’t really convey the symbolic quality that was expected of it, and sometimes jarred with the bolder use of distressed footage. It was these sequences where the band seemed happiest, letting rip against a furious cavalcade of distorted images. On other occasions it seemed constrained by the need to follow the film, and one sensed that the audience would have been content just to have had the band play and never mind the film.

That’s a shame, because it was a bold coming together of experimental film and post-bop jazz, telling a familiar story in an imaginatively oblique fashion. And it was a modern silent film, given its own spark of being by Douglas’ music. I especially admire Douglas’ imaginative vision of the silent film as a springboard for musical invention, which has taken him from Keaton and Arbuckle’s Moonshine to Bill Morrison with the same band, Keystone. Certainly Sunday night would have comes as a surprise to Mack Sennett.

Silent films will survive for many reasons, but one of them is music. They are always going to sound new, to have a connection with our times, so long as we keep on re-imagining how we want to make them sound. It is a key to their enduring appeal to the imagination.

Spark of Being, from http://www.fest21.com