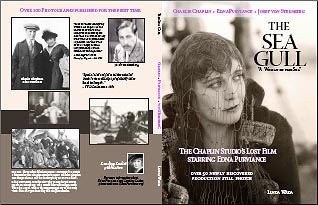

Hungary 1921

Director: Lajthay Károly

Production company: Corvin Filmgyár

Cinematographer: Eduard Hoesch

Scenario: Lajthay Károly, Mihály Kertész (Michael Curtiz)

Based on the character created by Bram Stoker

Cast: Paul Askonas (Drakula), Margit Lux (Mary Land), Elemér Thury (Doctor), Lajos Réthey (Fake doctor), Aladár Ihász (Assistant), Karl Götz (Funny man), Dezsö Kertész (George), Lajos Szalkay, Zoltán Dezső, Hatvani Károly, Oszkár Perczel, Károly Hatvani, Anna Marie Hegener, Paula Kende, Lene Myl, Magda Sonja, Béla Tímár

Five reels

Distributor: Jenö Tuchten

Poster for Drakula halála

Welcome all to the final screening in the inaugural Bioscope Festival of Lost Films. This evening we find ourselves in Leicester Square, in the cinema that has the honour of being the first such venue to have opened in London’s motion picture heartland. It was the 5th June 1909 when it first opened its doors, as the select Bioscopic Team Rooms. Soon it changed its name to the Circle in the Square, which name we rather prefer to its later name of the Palm Court Cinema, still more to its eventual fate – conversion into an Angus Steak House. There is room for 250 of you (if some stand), and the music is provided by the indefatigable and certainly inimitable Ena Baga.

And what a chilling offering we have for you tonight. It is with some pride (and not a little trepidation for fear of the effect it might have on some of the more nervous among you) that we present Drakula halála, a Hungarian tale of horror and fantasy as mysterious in its history as it is in its subject matter. Mystery, for example, surrounds the date of its production, but we are assured that – despite the several claims for it to have been made two years later – Drakula halála was produced in 1921 and was reportedly first shown in Vienna that year, though it was re-exhibited in Budapest in 1923. So the estimable F.W. Murnau in Germany who we hear is planning a film based on the legend of Dracula may have more resources at his disposal, yet he will be second with his subject matter. But finding any certain facts about our film’s production has been difficult (having no one on the Festival staff with a working knowledge of Hungarian has been a handicap).

Paul Askonas (Drakula) and Margit Lux (Mary)

The title of the film translates as The Death of Dracula, but the story is not that of the novel by Bram Stoker. Instead it tells of the orphaned Mary who is sent against her will to a psychiatric hospital. There one of the inmates claims to be the undead Dracula, and he begins to haunt her dreams. Although she escapes from the hospital and eventually marries a noble forester, visions of Dracula still fill her mind, and she remains unsure whether all that happened to her was some awful dream or horrid reality.

The Hungarian film industry is a modest one, and one that has suffered greatly under the political turmoil in that country. In 1919, the revolutionary Béla Kun established a Communist government, which collapsed after just a few months, to be replaced by the brutal military regime of Miklós Horthy. Kun had nationalised the film industry and an ambitious plan of production was drawn up. But the anti-Semitic Horthy despised the film industry, and persecuted many filmmakers (the unfortunate director Sándor Pallós was tortured to death for having made a film based on a novel by Gorky). Many in the industry fled, such as Sándor László Kellner (Alexander Korda) and Mihály Kertész (Michael Curtiz), who is believed to have contributed to the script of Drakula halála. The industry continues, but in a greatly reduced state, close to the point of bankruptcy.

Paul Askonas as Drakula

Thus Drakula halála is one of just a handful of films being made in Hungary at this time. Most are based on light popular novels, but this film is very different. Its star, Paul Askonas, has appeared in both Hungarian and Austrian films, usually of a fantastical or horrific nature, such as Labyrinth des Grauens (1921, Labyrinth of Horror). It is tempting to see this vision of dark threats, uncertainty and nightmares as somehow reflecting its troubled land and film industry, a place where reality may be a still greater nightmare than those encountered in one’s dreams. Director Lajthay Károly, a specialist in thrillers and someone praised for his uniquely atmospheric style, never directed another film – why, and whatever happened to him? (There are rumours of a drink problem) So many mysteries, so many more fantasies than certain facts…

Hungary is the land of lost silent films. 600 films made between 1912 and 1930, and just forty-five complete films survive. Drakula halála is not among them – or is it? Are we to believe the claims of a dubious Italian site dealing mostly in adult films, which claims to know of a 16mm print with a thirteen-minute fragment of the film? We choose not to believe it. The internet is awash with such fantasies. Here at the Bioscope Festival of Lost Films we deal only with true loss. Only when a film can no longer be seen does it, for us, become strangely, truly alive. Undead, even.

Publicity sheet for Life Without Soul, from http://frankensteinia.blogspot.com

To accompany this film we have broken our rules somewhat and gone for another five-reel feature rather than a short. But what a double-bill, to be able to offer you: Drakula halála and Life Without Soul. This 1915 film, made by the Ocean Film Corporation of New York, is similar to our main feature in that it presents the story of Frankenstein as a dream that explores the borderland between life and death. Frankenstein’s name has become William Frawley, a doctor living in modern times who dreams that he creates a humanoid monster (played by Percy Darrell). Despite acclaim for Mr Darrell’s chilling portrayal of a man without a soul that yet catches the audience’s sympathy, the film has not been a success. We hear that its 1916 re-edited re-issue included extra scenes taken from scientific films about the reproductive habits of fish. It is unclear why.

Do not believe the fantasist who on that modern innovation the Internet Movie Database, writes about this film as though he has seen it. He has not. It is lost, as have been all the films in this Bioscope Festival of Lost Films. We hope that you have enjoyed our selections. Please leave the cinema quietly, and a safe journey home to you all.

Pleasant dreams.