Germany 1925

Director: Hans Neumann

Production Company: Neumann-Film-Produktion GmbH (Berlin)

Producer: Hans Neumann

Screenplay: Hand Behrendt, Hans Neumann

Titles: Alfred Henschke

Cinematographer: Guido Seeber

Camera assistant: Reimar Kuntze

Costumes and sets: Ernö Metzner

Original music: Hans May

Cast: Theodor Becker (Theseus), Paul Günther (Egeus), Charlotte Ander (Hermia), André Mattoni (Lysander), Barbara von Annenkoff (Helena), Hans Albers (Demetrius), Bruno Ziener (Milon), Ernst Gronau (Squenz), Werner Krass (Zettel), Wilhelm Bendow (Flaut), Fritz Rasp (Schnauz), Walter Brandt (Schnock), Armand Guerra (Wenzel), Martin Jacob (Schlucker), Tamara (Oberon), Lori Leux (Titania), Valeska Gert (Puck), Alexander Granach (Waldschraff), Rose Veldtkirch, Adolf Klein, Hans Behrendt, Paul Biensfeldt

2,529 metres

The tragedy of Pyramus and Thisbe, from Ein Sommernachtstraum

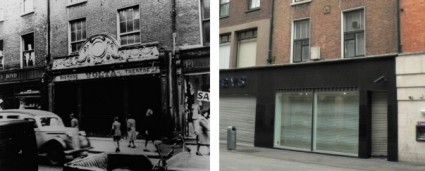

Welcome to day two of the Bioscope Festival of Lost Films, and to our special venue this evening, the Court Electric Theatre in London’s Tottenham Court Road. Opened in 1911, this select venue seats 420, and normally its patrons are entertained by an Italian orchestra. For this evening, however, to play the special music composed by Hans May for our lost film, we have Eric Borchard’s American jazz band, brought over at great expense following their acclaimed performances accompanying the film in Berlin.

And what a treat we have for you. Ein Sommernachstraum is a fascinating film, strangely and undeservedly forgotten by the posterity that is to come. It is, of course, based on William Shakespeare’s comedy, A Midsummer Night’s Dream, which is the title it has been given in America, though in Britain it has been rather curiously renamed Wood Love. It is the last silent film to be made of a Shakespeare play, and one of the oddest of that distinctly odd genre.

The plot, as you will know, revolves around two pairs of Athenian lovers, whose fortunes are mixed up with the fairy band of the forest and a group of comic workmen rehearsing a play, whose performance forms the uproarious conclusion to both film and play. However, the film takes numerous liberties with Shakespeare, as you will see. The character Shakespeare calls Bottom is here called Zettel, and is played by the great Werner Krauss (who you will recall played Iago in the 1922 German version of Othello and Shylock in the 1926 Der Kaufmann von Venedig). Oberon is played by a woman, the Russian ballet dancer Tamara. A battle between Greek warriors and the female Amazon army is shown, such as Shakespeare never thought to stage. Theseus is seen using a telephone.

Indeed this is not a conventional, nor respectful interpretation. It satirises the performance of Shakespeare, and the rather confused critics have variously described it as being ribald, charming, stagey, sincere, magical, dull, and grotesque. The Berlin censors pronounced it as being forbidden to juveniles. That this is intentionally a radical production can be seen from the presence of contributors such as the well-known poet and critic Alfred Henschke, writing the titles which slyly parody Shakespeare, while director Hans Neumann has been previously distinguished as a producer of titles such as Robert ‘Caligari’ Weine’s strikingly expressionist Raskolnikov. Yet some critics see it only as being conventionally charming, with such magical features as double exposures for appearing and disappearing fairy folk.

The British critic Oswald Blakeston has had some curious things to say about the film in the journal Close-up:

We all know the respectable whose lives are led in a patch of arid ground shut in by a complicated geometrical pattern of lines. Valeska Gert [playing Puck] steps beyond the lines as a hierophant to show what fun one can get from being released; Krauss steps beyond the lines to show what a great actor he is. The Gert puts out her tongue at the audience in devilment; the Krauss puts out his tongue for the audience to see how well he can act the part of a devil … There are more things in this picture more ineluctably Rabelasian that I have ever discovered in the most boisterous Rabelasian comedy … The heartiness in this picture is not biased, it spreads to the simple pleasure of hacking a man in two with a battle-axe.

We are not entirely sure what Mr Blakeston is on about (and we will leave you the pleasure of seeking out a dictionary to find out what ‘hierophant’ means), but clearly the film is a challenge to the senses.

And let us not forget the music. Hans May’s music, performed by jazz band with strings, has divided opinion, but Variety calls it “a real advance in scores for accompanying comedy pictures”. May playfully combines Wagner with Tin Pan Alley, closely scoring for such comic scenes as the battle with the Amazons, and frequently in performance the audience has burst into applause at the musical flourishes alone. As with the intertitles, the music forms an ironic commentary on Shakespeare’s play.

The film has enjoyed a long run at Berlin’s Nollendorf Platz theatre, where it has appeal for a discerning audience, but doubts must be expressed whether it can enjoy a similar kind of success in America or Britain. We are very pleased to be screening it here this evening, but feel that no film burdened with the title Wood Love will last long in the British cinemas.

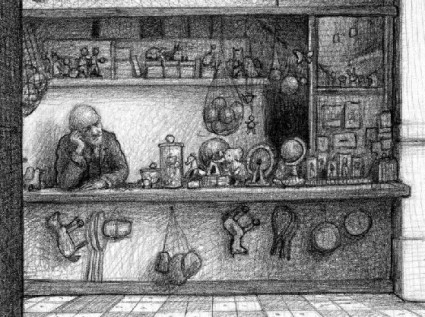

Georges Méliès contemplates Yorick’s skull

The lost short that accompanies Ein Sommernachtstraum is an appropriate one: Hamlet (France 1907). How wonderful to see the great Georges Méliès play the Dane! How wonderful too to have Shakespeare’s greatest, but undoubtedly lengthy play, brought to a far more manageable and agreeable length of ten minutes. All the essential details are there: Hamlet at the graveside, his madness aggravated by the sight of visions, Hamlet meeting his father’s ghost, Hamlet meeting the ghost of his love Ophelia, the duel before King Claudius, and the death of Hamlet. Clearly the film displays a bold use of flashbacks and much of M. Méliès’ favoured use of camera trickery. One great artist putting his distinctive stamp upon the work of another.

So ends our screening for this evening. Be sure to return tomorrow, when we shall be at the Casino de Paris to see a truly sensational American production.