Francis Martin Duncan with microcinematographical equipment

Opening today is an exhibition at the Science Museum on the history of the science film. Entitled Films of Fact, it looks at the development of scientific films and television programmes from 1903 to 1965. Its subject, and that of the book that accompanies it, is not really scientific film as in film used in the study of science, but rather the presentation of science on film. So it’s about popularisation and communication.

Films of Fact as a title comes from the name of the company of social documentarist Paul Rotha, once renowned not just as a filmmaker but as a theorist and film historian. But the exhibition also focuses on an earlier period, when science film meant films of nature, and it has generated quite a bit of press interest in one film in particular, Cheese Mites, made by zoologist Francis Martin Duncan in 1903 using microcinematopgrahic equipment (microscope + cine camera, basically) for producer Charles Urban. Urban had had the extraordinary idea of putting science films before a music hall audience, in a show he called The Unseen World. This contemporary review from the Daily Telegraph gives an idea of the astonished audience reaction:

Science has just added a new marvel to the marvelous powers of the Bioscope. A few years ago it was thought sufficiently wonderful to show the picture of a frog jumping. Go to the Alhambra this week and you may seen upon the screen the blood circulating in that same frog’s foot. This sounds a trifle incredible, but it is an exact statement of the truth. The new miracle has been performed by the adaptation of the microscope to the camera which takes the Bioscope films. Last night The Charles Urban Trading Company Ltd, who has taken the photographs, had many other miracles to show and explain to a fascinated audience. There was a blood-curdling picture of cheese-mites taking their walks abroad, the tiny creatures looking on the screen as large as small crabs. The minute hydra which lives in stagnant water appeared shooting out its tentacles and taking a meal … Twenty-five minutes, the length of the exhibition, is a long time to give to a Bioscope turn, but the rapt attention of the audience and the thunders of applause at the conclusion testified to the way in which popularity had been at once secured by these unique pictures.

Cheese Mites (1903)

Cheese Mites was the hit of the show, and is only one the Unseen World films to survive (the BFI has it). Originally the film just showed the magnified creatures. Later Urban added a comic framing story, as this Charles Urban Trading Company catalogue entry explains:

A gentleman reading the paper and seated at lunch, suddenly detects something the matter with his cheese. He examines it with his magnifying glass, starts up and flings the cheese away, frightened at the sight of the creeping mites which his magnifying glass reveals. A ripe piece of Stilton, the size of a shilling, will contain several hundred cheese mites. In this remarkable film, the mites are seen crawling and creeping about in all directions, looking like great uncanny crabs, bristling with long spiny hairs and legs.

Unfortunately, these extra scenes don’t survive. There’s a news report on the BBC site about the exhibition, which include the Cheese Mites film, so do take a look, and ponder the alarm that was said at the time to have spread among cheese manufacturers, who begged for the film to be stopped being shown. There’s also an article in this week’s New Scientist magazine which tells the story behind the film and that of Percy Smith, a later collaborator with Charles Urban, who made such classics as The Balancing Bluebottle (1908) and The Birth of a Flower (1910), employing time-lapse photography, before going on to make the once-famous series The Secrets of Nature in the 1920s and 1930s.

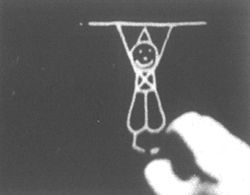

The Acrobatic Fly (a retitled version of The Balancing Bluebottle), made by Percy Smith in 1908. As Smith explained, “The fly is quite uninjured and is merely supported by a silken band when performing with weights which would otherwise overbalance it. When its feats are accomplished it is allowed to fly away.”

And then there’s the book. Timothy Boon’s Films of Fact: A History of Science in Documentary Film and Television is something quite special. It’s a history of a type of film which has barely been covered by historians, and has much that is new or revalatory, for the silent era and beyond. But it’s also a cultural history, which addresses why these films were made, what the popularisation of science means, and how science relates to society at large. It’s an exciting read, and I’ll try and give it more space at another time, while looking at the literature of the early science film in general. Anyway, Charles Urban, F. Martin Duncan and Percy Smith are the flavour of the moment, which is unexpected but should be fun while it lasts. I saw Cheese Mites and Percy Smith’s The Acrobatic Fly shown before an audience this evening, and they excited much the same mixture of amusement and amazement as they did a century ago. The filmmakers of old did know a thing or two.

The Science Museum exhibition runs until February 2009.