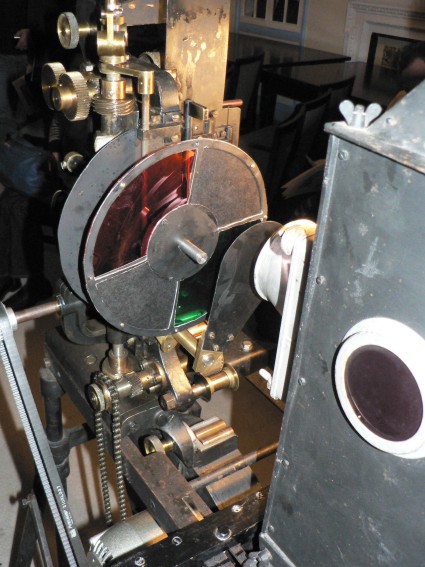

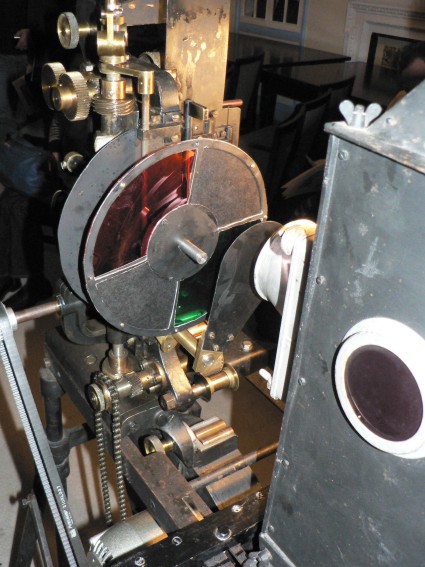

David Cleveland operating a Kinemacolor projector

We continue with our series on the history of early colour cinematography, but take a diversion out of the past to the present day – Monday February 25th, to be precise – for the very best of reasons. Because today, at the British Film Institute’s J. Paul Getty Conservation Centre in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire, we witnessed a rare recreation of ‘true’ Kinemacolor.

The screening was organised by film archivists David Cleveland and Brian Pritchard, who decided to mark the centenary of Kinemacolor by exhibiting the world’s first natural colour motion picture system in its correct form, using an original Kinemacolor projector. Kinemacolor films have been shown in composite colour or computer synthesized forms, or so customised that they will run at normal speed on a normal projector, but not since 1995 at the Museum of the Moving Image has anyone attempted to show Kinemacolor as it was originally done – black-and-white film run through a projector fitted with a red and green rotating filter, at double speed (thirty or more frames per second). It is rarer still to employ an original projector (the MOMI show used a customised 1920s Ernemann projector).

Kinemacolor projector no. 19 (rear view showing colour filter)

The projector was generously loaned by Wirral Museum, which also allowed the archivists to replace missing parts and to make the machine operable, so long as it would be returned to its original museum state once they had finished with it. It is Kinemacolor projector no. 19, with original colour filter. Cleveland and Pritchard aimed to be as authentic as possible, with two limitations – they could not show nitrate films, fairly obviously, and for similar health and safety reasons they could not use an arc light (they used a filament blub instead).

We gathered in a small room, with chandelier adding an appropriate touch of class to the proceedings (less so the windows necessarily blacked out with black bags and tape). The small audience comprised archivists from the BFI National Archive, a smattering of academics, and as guests of honour, Kinemacolor’s producer Charles Urban’s step-grandson Bruce Mousell and his two daughters.

David introduced the event and the projector, then we were shown three of the sample Kinemacolor films held in the BFI National Film Archive. Tragically few Kinemacolor films survive today, and all that the UK’s national archive holds are some test films which were never shown publicly. These were retained by the system’s inventor G.A. Smith, who passed them on to Brighton collector Graham Head, whose collection in turn went to the Cinema Museum in London. Two of the prints we saw were therefore struck from original negatives, with a third taken from a dupe neg. This film was shown first, Cat Studies (c.1908), a short single shot of a cat (a black-and-white cat at that), which served to help make adjustments to the filter, since we started off with the wooden board with a hole through which the cat looked appearing green, because the rotating filter had been aligned incorrectly.

Projection of Kinemacolor test film Woman Draped in Patterned Handkerchiefs

There then followed Woman Draped in Patterened Handkerchiefs (c.1908), whose action is self-explanatory, a film clearly designed to demonstrate basic colour effects; and Pageant of New Romney, Hythe and Sandwich (1910), an actuality film rejected at the time for being too contrasty. In truth, the sample Kinemacolor films held by the BFI are poor examples of the colour system, showing little in the way of effective colour, and the latter film in particular demonstrating the hazards of fringing (the alternating red/green records meant that the film record could not always keep up with movement, resulting in red or green ‘fringes’).

But, after a pause for reloading and a talk from Brian Pritchard on the customising of the projector and Smith’s ingenious use of sensitizing chemicals (without which Kinemacolor would not have worked at all), we were shown a beautiful Kinemacolor film loaned by the Nederlands Filmmuseum. This was Lake Garda, Italy (1910), a travelogue of the Italian beauty spot, whose picture postcard images showed up the colour to exquisite effect. We saw panoramic views of the lake, buildings, boats with red and yellow sails, and a delightful sequence where three musicians in a small boat serenaded the camera. Being full of gentle motion, the muted, subtle colour was shown to its best effect, being particularly good at rendering white buildings and reflections in the water. Kinemacolor, using as it did red and green filters, could not logically depict blue, yet blue we saw in the sky and water. This is all down to our gullible brains, reconstituting what seems optically logical to us. The sky should be blue, so we see blue.

What was also interesting was the colossal noise. The motorised projector had to rattle through at a speed of thirty frames per second, and the racket drowned out all conversation. The image on the screen had to be kept quite small, to retain as much brightness as possible (Kinemacolor absorbs a great deal of light). We all wondered how on earth they coped projecting Kinemacolor in large theatres, where the throw would have been considerable. We also marvelled at the skill of the original projectionists, who had to cope not only with a double-speed projector, but changing colour effects owing to differences in filters used (the cameramen would change then accoding to the light conditions encountered) and all of the hazards of correct colour synchronisation.

David Cleveland (right) with Charles Urban’s step-grandson Bruce Mousell and his daughters

The demonstration revealed many of the problems, but also several of the beauties of Kinemacolor, and made one wish for more such screenings to be organised. As David Cleveland explained in his notes to the show:

Several archives have a few examples of Kinemacolor films in their collections, and the usual process is to make a composite film copy of the red and green images onto one new Eastman Color inter-negative, and normal colour prints therefrom. Of course this takes on Eastman Color characteristics, and the colour is not the same as originally seen. Scanning is probably the answer, but here again it needs to be carefully done so that the colour is as near to the original filters as possible … and that the result is not a smooth ‘television’ type picture, but an image that resembles the projected picture of a century ago. Only this way can Kinemacolor be put into context with the development of colour films.

It is a great shame that, in its centenary year, Kinemacolor remains so elusive. Cleveland and Pritchard had the greatest difficulty getting films from other archives, and it is to be hoped that there may be greater co-operation over any future events. So few Kinemacolor films survive (maybe thirty or so, out of the hundreds originally produced), and more must be done to preserve them, to make them accessible in original as well as the more convenient composite form, and to uncover more – because there are undoubtedly ‘lost’ Kinemacolor films out there. Kinemacolor appears to be ordinary silent black-and-white film to the untrained eye. Only when you look closely do you see alterations in tonal emphasis from frame to frame. Many archives, I am sure, are sitting on Kinemacolor films and are not aware of the fact. 2008 would be a good year in which to start conducting a search to locate them.