The outstanding Flicker Alley 5-disc set Georges Méliès: First Wizard of Cinema (1896-1913) is now published, and I have my copy. Naturally, it’s a sensational package. Put together by Eric Lange (Lobster Films) and David Shepard (Blackhawk Films) from the archival holdings from seventeen collections across eight countries, the elegantly-presented DVDs comprises 173 titles (including one unidentified fragment) – almost (though not quite) every extant Georges Méliès film, plus the Georges Franju 1953 film, Le Grand Méliès. The DVDs are region 0, NTSC format.

The set comes with a well-illustrated booklet, which has essays by Norman McLaren (something of a surprise – it’s a transcript of an audio recording he made for a conference he couldn’t attend) and a long piece by John Frazer on Méliès’ life and work, adapted by Shepard from a text first written by Frazer in 1979. The full list of titles is now available on the Flicker Alley site, but here’s The Bioscope’s version, with the titles in the chronological order in which they appear on the DVDs, with Star-Film catalogue number, original French title and English title.

1896

1 – Partie de cartes, une/Playing Cards

26 – Nuit terrible, une/Terrible Night, a

70 – Escamotage d’une dame chez Robert-Houdin/Vanishing Lady, the

82 – Cauchemar, le/Nightmare, A

1897

96 – Château hanté, le/Haunted Castle, The

106 – Prise de Tournavos, la/Surrender of Tournavos, The

112 – Entre Calais et Douvres/Between Calais and Dover

122-123 – Auberge ensorcelée, l’/Bewitched Inn, the

128 – Après le bal (le tub)/After the Ball

1898

147 – Visite sous-marine du Maine/Divers at Work on the Wreck of the “Maine”

151 – Panorama pris d’un train en marche/Panorama from Top of a Moving Train

153 – Magicien, le/Magician, The

155 – Illusions fantasmagoriques/Famous Box Trick, The

159 – Guillaume Tell et le clown/Adventures of William Tell, The

160-162 – Lune à un mètre, la/Astronomer’s Dream, The

167 – Homme de têtes, un/Four Troublesome Heads, The

169 – Tentation de Saint Antoine/Temptation of St Anthony, the

Entrevue de Dreyfus et de sa femme à Rennes

1899

183 – Impressionniste fin de siècle, l’/Conjurer, The

185-187 – Diable au couvent, le/Devil in a Convent, The

188 – Danse du feu/Pillar of Fire, The

196 – Portrait mystérieux, le/Mysterious Portrait, The

206 – Affaire Dreyfus, la dictée du bordereau/Dreyfus Court Martial – Arrest of Dreyfus

207 – Ile du diable, l’/Dreyfus: Devil’s Island – Within the Palisade

208 – Mise aux fers de Dreyfus/Dreyfus Put in Irons

209 – Suicide du Colonel Henry/Dreyfus: Suicide of Colonel Henry

210 – Débarquement à Quiberon/Landing of Dreyfus at Quiberon

211 – Entrevue de Dreyfus et de sa femme à Rennes/Dreyfus Meets His Wife at Rennes

212 – Attentat contre Me Labori/Dreyfus: The Attempt Against the Life of Maître Labori

213 – Bagarre entre journalistes/Dreyfus: The Fight of Reporters

214-215 – Conseil de guerre en séance à Rennes, le/Dreyfus: The Court Martial at Rennes

219-224 – Cendrillon/Cinderella

226-227 – Chevalier mystère, le/Mysterious Knight, The

234 – Tom Whisky ou l’illusionniste truqué/Addition and Subtraction

L’Homme-orchestre

1900

243 – Vengeance du gâte-sauce, la/Cook’s Revenge, The

244 – Infortunes d’un explorateur, les/Misfortunes of an Explorer, The

262-263 – Homme-orchestre, l’/One-Man Band, The

264-275 – Jeanne d’Arc/Joan of Arc

281-282 – Rêve du Radjah ou la forêt enchantée, le/Rajah’s Dream, The

285-286 – Sorcier, le prince et le bon génie, le/Wizard, the Prince and the Good Fairy, The 289-291 – Livre magique/Magic Book, The

293 – Spiristisme abracadabrant/Up-to-date Spiritualism

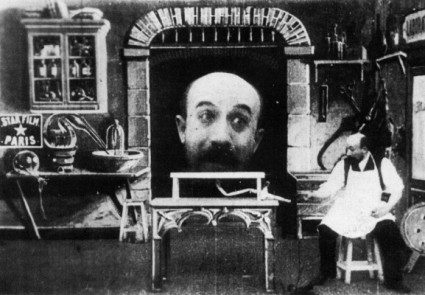

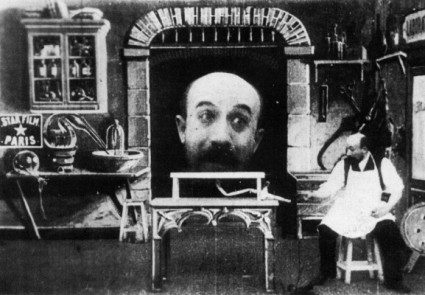

294 – Illusioniste double et la tête vivante, l’/Triple Conjurer and the Living Head, The

298-305 – Rêve de Noël/Christmas Dream, The

309-310 – Nouvelles luttes extravagantes/Fat and Lean Wrestling Match

311 – Repas fantastique, le/Fantastical Meal, A

312-313 – Déshabillage impossible, le/Going to Bed under Difficulties

314 – Tonneau des Danaïdes, le/Eight Girls in a Barrel

317 – Savant et le chimpanzé, le/Doctor and the Monkey, The

322 – Réveil d’un homme pressé, le/How He Missed His Train

L’Homme à la tête en caoutchouc

1901

325-326 – Maison tranquille, la/What is Home Without the Boarder?

332-333 – Chrysalide et le papillon, la/Brahmin and the Butterfly, The

335-336 – Dislocation mystérieuse/Extraordinary Illusions

345-347 – Antre des esprits, le/Magician’s Cavern, The

350-351 – Chez la sorcière/Bachelor’s Paradise, The

357-358 – Excelsior!/Excelsior! – Prince of Magicians

361-370 – Barbe-Bleue/Blue Beard

371-372 – Chapeau à surprises, le/Hat With Many Surprises, The

382-383 – Homme à la tête en caoutchouc, l’/Man With the Rubber Head, The

384-385 – Diable géant ou le miracle de la madone, le/Devil and the Statue, The

386 – Nain et géant/Dwarf and the Giant, The

Voyage dans la lune

1902

391 – Douche du colonel/Colonel’s Shower Bath, The

394-396 – La danseuse microscopique, la/Dancing Midget, The

399-411 – Voyage dans la lune/Trip to the Moon, A

412 – Clownesse fantôme, la/Shadow-Girl, The

413-414 – Trésors de Satan, les/Treasures of Satan, The

415-416 – Homme-mouche, l’/Human Fly, The

419 – Équilibre impossible, l’/Impossible Balancing Feat, An

426-429 – Voyage de Gulliver à Lilliput et chez les géants, le/Gulliver’s Travels Among the Lilliputians and the Giants

No number – Sacre d’Edouard VII, le/Coronation of Edward VII, The

445-448 – Guirlande merveilleuse, la/Marvellous Wreath, The

1903

451-452 – Malheur n’arrive jamais seul, un/Misfortune Never Comes Alone

453-457 – Cake-walk infernal, le/Infernal Cake-Walk, The

458-459 – Boîte à malice, la/Mysterious Box, The

462-464 – Puits fantastique, le/Enchanted Well, The

465-469 – Auberge du bon repos, l’/Inn Where No Man Rests, The

470-471 – Statue animée, la/Drawing Lesson, The

473-475 – Sorcier, le/Witch’s Revenge, The

476 – Oracle de Delphes, l’/Oracle of Delphi, The

447-478 – Portrait spirite, le/Spiritualistic Photographer

479-480 – Mélomane, le/Melomaniac, The

481-482 – Monstre, le/Monster, The

483-498 – Royaume des fées, le/Kingdom of the Fairies, The

499-500 – Chaudron infernal, le/Infernal Cauldron, The

501-502 – Revenant, le/Apparitions

503-505 – Tonnerre de Jupiter, le/Jupiter’s Thunderbolts

506-507 – Parapluie fantastique, le/Ten Ladies in an Umbrella

508-509 – Tom Tight et Dum Dum/Jack Jaggs and Dum Dum

510-511 – Bob Kick, l’enfant terrible/Bob Kick the Mischievous Kid

512-513 – Illusions funambulesques/Extraordinary Illusions

514-516 – Enchanteur Alcofribas, l’/Alcofribas, the Master Magician

517-519 – Jack et Jim/Comical Conjuring

520-524 – Lanterne magique, la/Magic Lantern, The

525-526 – Rêve du maître de ballet, le/Ballet Master’s Dream, The

527-533 – Faust aux enfers/Damnation of Faust, The

534-535 – Bourreau turc, le/Terrible Turkish Executioner, The

538-539 – Au clair de la lune ou Pierrot malheureux/Moonlight Serenade, A

540-541 – Prêté pour un rendu, un/Tit for Tat

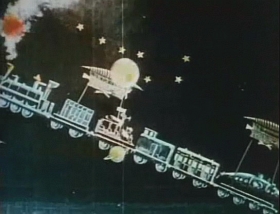

Voyage à travers l’impossible

1904

547-549 – Coffre enchanté, le/Bewitched Trunk, The

552-553 – Roi du maquillage, le/Untamable Whiskers

554-555 – Rêve de l’horloger, le/Clockmaker’s Revenge, The

556-557 – Transmutations imperceptibles, les/Imperceptible Transmutations, The

558-559 – Miracle sous l’Inquisition, un/Miracle Under the Inquisition, A

562-574 – Damnation du Docteur Faust/Faust and Marguerite

578-580 – Thaumaturge chinois, le/Tchin-Chao, the Chinese Conjurer

581-584 – Merveilleux éventail vivant, le/Wonderful Living Fan, The

585-588 – Sorcellerie culinaire/Cook in Trouble, The

589-590 – Planche du diable, la/Devilish Prank, The

593-595 – Sirène, la/Mermaid, The

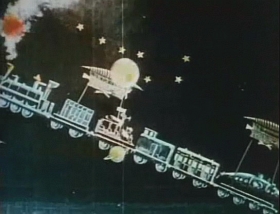

641-659 – Voyage à travers l’impossible/Impossible Voyage, The

665-667 – Cascade de feu, la/Firefall, The

678-679 – Cartes vivantes, les/Living Playing Cards, The

1905

683-685 – Diable noir, le/Black Imp, The

686-689 – Phénix ou le coffret de cristal, le/Magic Dice, The

690-692 – Menuet lilliputien, le/Lilliputian Minuet, The

705-726 – Palais des mille et une nuits, le/Palace of the Arabian Nights, The

727-731 – Compositeur toqué, le/Crazy Composer, A

738-739 – Chaise à porteurs enchantée, la/Enchanted Sedan Chair, The

740-749 – Raid Paris – Monte-Carlo en deux heures, le/Adventurous Automobile Trip, An

756-775 – Légende de Rip Van Vinckle, la/Rip’s Dream

784-785 – Tripot clandestin, le/Scheming Gamblers’ Paradise, The

789-790 – Chute de cinq étages, une/Mix-up in the Gallery, A

791-806 – Jack le ramoneur/Chimney Sweep, The

807-809 – Maestro Do-Mi-Sol-Do, le/Luny Musician, The

1906

818-820 – Cardeuse de matelas, la/Tramp and the Mattress Makers, The

821-823 – Affiches en goguette, les/Hilarious Posters, The

824-837 – Incendiaires, les/Desperate Crime, A

838-839 – “Anarchie chez Guignol, l'”/Punch and Judy

843-845 – Hôtel des voyageurs de commerce ou les suites d’une bonne cuite, l’/Roadside Inn, A

846-848 – Bulles de savon animées, les/Soap Bubbles

849-870 – Quatre cents farces du diable, les/Merry Frolics of Satan, The

874-876 – Alchimiste Parafaragaramus ou la cornue infernale, l’/Mysterious Retort, The

877-887 – Fée Carabosse ou le poignard fatal, la/Witch, The

L’Tunnel sous la Manche ou le cauchemar anglo-français

1907

909-911 – Douche d’eau bouillante, la/Rogues’ Tricks

925-928 – Fromages automobiles, les/Skipping Cheeses, The

936-950 – Tunnel sous la Manche ou le cauchemar anglo-français, le/Tunnelling the English Channel

961-968 – Eclipse de soleil en pleine lune/Eclipse, or the Courtship of the Sun and Moon, The

1000-1004 – Pauvre John ou les aventures d’un buveur de whisky/Sightseeing through Whisky

1005-1009 – Colle universelle, la/Good Glue Sticks

1014-1017 – Ali Barbouyou et Ali Bouf à l’huile/Delirium in a Studio

1030-1034 – Tambourin fantastique, le/Knight of Black Art, The

1035-1039 – Cuisine de l’ogre, la/In the Bogie Man’s Cave

1044-1049 – Il y a un dieu pour les ivrognes/Good Luck of a Souse, The

1066-1068 – Torches humaines/Justinian’s Human Toches 548 A.D.

1908

1069-1072 – Génie du feu, le/Genii of the Fire, The

1073-1080 – Why that actor was late

1081-1085 – Rêve d’un fumeur d’opium, le/Dream of an Opium Fiend, The

1091-1095 – Photographie électrique à distance, la/Long Distance Wireless Photography

1096-1101 – Prophétesse de Thèbes, la/Prophetess of Thebes, The

1102-1103 – Salon de coiffure/In the Barber Shop

1132-1145 – Nouveau seigneur du village, le/New Lord of the Village, The

1146-1158 – Avare, l’/Miser, The

1159-1165 – Conseil du Pipelet ou un tour à la foire, le/Side Show Wrestlers

1176-1185 – Lully ou le violon brisé/Broken Violin, The

1227-1232 – The Woes of Roller Skates

1246-1249 – Amour et mélasse/His First Job

1250-1252 – Mésaventures d’un photographe, les/The Mischances of a Photographer

1253-1257 – Fakir de Singapour, le/Indian Sorcerer, An

1266-1268 – Tricky painter’s fate, a

1288-1293 – French interpreter policeman/French Cops Learning English

1301-1309 – Anaïc ou le balafré/Not Guilty

1310-1313 – Pour l’étoile S.V.P./Buncoed Stage Johnnie

1314-1325 – Conte de la grand-mère et rêve de l’enfant/Grandmother’s Story, A

1416-1428 – Hallucinations pharmaceutiques ou le truc du potard/Pharmaceutical Hallucinations

1429-1441 – Bonne bergère et la mauvaise princesse, la/Good Shepherdess and the Evil Princess

No number – unidentified film

1909

1495-1501 – Locataire diabolique, le/Diabolic Tenant, The

1508-1512 – Illusions fantaisistes, les/Whimsical Illusions

1911

1536-1547 – Hallucinations du Baron de Münchausen, les /Baron Munchausen’s Dream

1912

Pathé – A la conquète du pôle/Conquest of the Pole, The

Pathé – Cendrillon ou la pantoufle merveilleuse/Cinderella

Pathé – Chevalier des neiges, le/Knight of the Snow, The

1913

Pathé – Voyage de la famille Bourrichon, le/Voyage of the Bourichon Family, The

Almost needless to say, the quality of the digital transfers is excellent, sometimes startlingly so. There are fifteen examples of beautiful hand-colouring. Many musicians have provided scores, making the DVD a fascinating demonstration in itself of different approaches to the task of accompanying Georges Méliès (even if, for myself I find the American taste for organ accompaniment baffling). They are Eric Beheim, Brian Benison, Frederick Hodges, Robert Israel, Neal Kurz, the Mont Alto Motion Picture Orchestra, Alexander Rannie, Joseph Rinaudo, Rodney Sauer and Donald Sosin. Some of the films come with Georges Méliès’ original English narrations, designed to be spoken alongside the films, and here are spoken by Serge Bromberg and Fabrice Zagury (with some rather quaint mangling of the English language in places).

Georges Méliès is confirmed here as among the pre-eminent artists of the cinema, perhaps the most exuberant of all filmmakers. The films display imagination, wit, ingenuity, grace, style, fun, invention, mischief, intelligence, anarchy, innocence, vision, satire, panache, beauty and longing, the poetry of the absurd. Starting out as extensions of the tricks that made up Méliès’ magic shows, to view them in chronological order as they are here is to see the cinema itself bursting out of its stage origins into a theatre of the mind, where anything becomes possible – a true voyage à travers l’impossible, to take the title of one of his best-known films. The best of them have not really dated at all, in that they have become timeless, and presumably (hopefully) always will be so. Méliès in his lifetime suffered the agony of seeing his style of filmming turn archaic as narrative style in the Griffith manner became dominant, but we can see now that is his work that has truly lasted. The films will always stand out as showing how motion pictures, when they first did appeared, in a profound sense captured the imagination. And there is that consistency of vision that confirms Méliès as a true artist with a body of work that belongs in a gallery – or in this case a boxed set of DVDs – for everyone to appreciate.

What a great publication this is. Every good home should have one.

Update (January 2010):

For information on a sixth, supplementary disc with an additional 26 titles, see https://bioscopic.wordpress.com/2010/01/08/melies-encore.