Talking Silents, vols. 1-4

One of the great treasures available to anyone with a serious interest in the history of silent cinema is the Talking Silents series produced by Digital Meme. This is a series of ten DVDs of Japanese silents films, with two or three titles per disc. Silent cinema continued in Japan well into the 1930s, but survival rates for Japanese silents make for sorry reading. It is estimated that between 95-99% of all Japanese silent films are lost (with almost none before 1923 owing to the destruction of the Nikkatsu film store in the Tokyo earthquake). Those that do survive are often in a poor condition. Classics such as Kinugasa Teinosuke’s A Page of Madness (1926) and Yasujiro Ozu’s I Was Born But… (1932) are well-known, but what is so interesting about the Digital Meme series is that it includes comparatively routine genre works, so that one gets a real taste of popular Japanese silent cinema.

The striking feature of the series is the use of benshi narration. In the silent era (and even for a while the sound period), Japanese films were accompanied by narrators, an inheritance from the Japanese theatrical tradition. Originally each part in a film was taken by a separate off-screen performer, until the film industry rebelled against this theatrical domination, around 1920, and the single benshi tradition began. The benshi were the stars of Japanese silent cinema: audiences revered theme, and the performers developed individual styles. The DVDs include narrations from recordings made of benshi in the 1970s and 80s, and recreations of the style by Midori Sawato. The narration is an optional feature, and the films carry both the original Japanese titles and English translated titles.

The films present fine mixture of styles, including samurai tales and contemporary dramas, with some early titles from the great master Kenji Mizoguchi. This is full list:

Talking Silents 1:

* Taki no Shiraito (The Water Magician)

Produced by Irie Production, 1933

98 minutes / 24 fps

Directed by Kenji Mizoguchi

Cast: Takako Irie, Tokihiko Okada, Ichiro Sugai* Tokyo Koshinkyoku (Tokyo March)

Produced by Nikkatsu Uzumasa, 1929

28 minutes / 24 fps

Directed by Kenji Mizoguchi

Cast: Shizue Natsukawa, Reiji Ichiki, Isamu KosugiTalking Silents 2:

* Orizuru Osen (The Downfall of Osen)

Produced by Daiichi Eiga, 1935

90 minutes / 24 fps

Directed by Kenji Mizoguchi

Cast: Isuzu Yamada, Daijiro Natsukawa, Ichiro Yoshizawa* Tojin Okichi

Produced by Nikkatsu Uzumasa, 1930

4 minutes / 24 fps

Directed by Kenji Mizoguchi

Cast: Yoko UmemuraTalking Silents 3:

* Orochi (Serpent)

Produced by Bantsuma Production, 1925

74 minutes / 24 fps

Directed by Buntaro Futagawa

Cast: Tsumasaburo Bando, Misao Seki, Utako Tamaki* Gyakuryu (Backward Flow)

Produced by Toatojiin, 1924

28 minutes / 16 fps

Directed by Buntaro Futagawa

Cast: Tsumasaburo Bando, Benisaburo Kataoka, Teruko MakinoTalking Silents 4:

* Koina no Ginpei, Yuki no Wataridori (Koina no Ginpei, Migratory Snowbird)

Produced by Bantsuma Production, 1931

60 minutes / 24 fps

Directed by Tomikazu Miyata

Cast: Tsumasaburo Bando, Kikuya Okada, Reiko Mochizuki* Kosuzume Toge (Kosuzume Pass)

Produced by Makino Tojiin, 1923

39 minutes / 16 fps

Directed by Koroku Numata

Cast: Banya Ichikawa, Shinpei Takagi, Tsumasaburo BandoTalking Silents 5:

* Kurama Tengu

Produced by Arakan Production, 1928

71 minutes / 24 fps

Directed by Teppei Yamaguchi

Cast: Kanjuro Arashi, Takesaburo Nakamura,

Reizaburo Yamamoto, Kunie Gomi and Keiichi Arashi* Kurama Tengu Kyofu Jidai (The Frightful Era of Kurama Tengu)

Produced by Arakan Production, 1928

38 minutes / 16 fps

Directed by Teppei Yamaguchi

Cast: Kanjuro Arashi, Reizaburo Yamamoto, Kunie Gomi and Keiichi ArashiTalking Silents 6:

* Nishikie Edosugata Hatamoto to Machiyakko (The Color Print of Edo: Hatamoto to Machiyakko) (1939, Shinko Kinema, 65 min.)

Directed by Kazuo Mori

Cast: Utaemon Ichikawa, Yaeko Kumoi, Shinpachiro Asaka, Wakako Kunitomo* Dokuro (Skull) (1927, Ichikawa Utaemon Production, 32 min.)

Directed by Sentaro Shirai

Cast: Utaemon Ichikawa, Kokuten Takado, Ritsuko NiizumaTalking Silents 7:

* Oatsurae Jirokichi Koshi (Jirokichi the Rat) (1931, Nikkatsu, 61 min.)

Directed by Daisuke Ito

Cast: Denjiro Okochi, Naoe Fushimi, Nobuko Fushimi, Minoru Takase* Yajikita Sonno no Maki (Yaji and Kita: Yasuda’s Rescue) (1927, Nikkatsu, 15 min.)

Directed by Tomiyasu Ikeda

Cast: Goro Kawabe, Denjiro Okochi* Yajikita Toba Fushimi no Maki (Yaji and Kita: The Battle of Toba Fushimi(1928, Nikkatsu, 8 min.)

Directed by Tomiyasu Ikeda

Cast: Goro Kawabe, Denjiro OkochiTalking Silents 8:

* Kodakara Sodo (1935, Shochiku Kamata, 33 min.)

Directed by Torajiro Saito

Cast: Shigeru Ogura, Yaeko Izumo* Akeyuku Sora (1929, Shochiku Kamata, 71 min.)

Directed by Torajiro Saito

Cast: Yoshiko Kawada, Mitsuko TakaoTalking Silents 9:

* Roningai Dai Ichiwa (1928, Makino Production, 8 min.)

Directed by Masahiro Makino

Cast: Komei Minami, Juro Tanizaki, Toichiro Negishi* Roningai Dai Niwa (1929, Makino Production, 72 min.)

Directed by Masahiro Makino

Cast: Komei Minami, Hiroshi Tsumura, Toichiro Negishi* Sozenji Baba (1928, Makino Production, 32 min.)

Directed by Masahiro Makino

Cast: Komei Minami, Shinpei Takagi, Toroku MakinoTalking Silents 10:

* Jitsuroku Chushingura (Chushingura: The Truth)

Produced by Makino Production, 1928, 64 min.

Directed by Shozo Makino

Cast: Yoho Ii, Tsuzuya Moroguchi, Kobunji Ichikawa, Yotaro Katsumi* Raiden

Produced by Makino Production, 1928, 18 min.

Directed by Shozo Makino

Cast: Toichiro Negishi, Arata Kaneko, Masahiro Makino

Talking Silents vols. 5-8

You get a little in the way of extras on each of the DVDs: a commentary from film critic Tadao Sato, an introduction by modern benshi Midori Sawato. The Digital Meme site has downloadable PDFs of introductions by Tadao Sato. The DVD booklets are thin and half in Japanese, half-English. What is noteworthy is the offer made to educational institutions. Digital Meme makes the series available under three prices: Home Use (allowing individual viewings), Rental Use (allowing institutions to give their members and affiliated persons the right to rent the collection and take it out of their libraries) and Institutional Screening Rights Agreement (for institutions that want to screen the DVDs to a public audience within their premises, or at an affiliate, on a non-commercial basis).

Digital Meme also make available a 1980 documentary on DVD on the life of film actor Tsumasaburo Bando, Bantsuma: The Life of Tsumasaburo Bando (Bantsuma: Bando Tsumasaburo no shogai), and a 4-DVD set Japanese Anime Classic Collection. This is a treasure trove of early Japanese animation, with some of the translated titles delightfully giving indication of their idiosyncratic content: The Tiny One Makes It Big, Dekobo the Big Head’s Road Trip, Why is the Sea Water Salty?, The Duckling Saves the Day. A section of the Digital Meme site gives details of each of the 55 titles on the four-disc set, with frame stills and some synopses. The set comes with English subtitles (and Chinese, and Korean), some live benshi narration, and examples of anime with synchronised audio tracks from gramophone records.

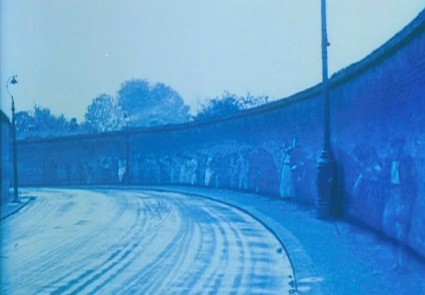

Dekobo no Jidosha Ryoko (Dekobo the Big Head’s Road Trip)

And there’s more. Digital Meme also markets Masterpieces of Japanese Silent Cinema, a DVD-Rom which includes extracts from forty-five films, a database of 12,000 film titles, almost 1,000 stills, posters, original programmes and leaflets, interviews with film veterans, and reference articles, making it an interactive encyclopedia of Japanese silent film, albeit at a price of 18,000 Yen (around $180) which means only institutions are likely to purchase it.

For more on Japanese silent cinema, here’s a few handy sources:

- Shunsui Matsuda, one of the benshi whose recordings are used in the Talking Silents series, wrote The Benshi – Japanese Silent Film Narrators, a companion piece to the DVD series (whose film source is Matsuda Film Productions)

- Matsuda also has a website on Japanese silents with a variety of resources and links to all the above selections and more

- Joanne Bernardi’s Writing in Light: The Silent Scenario and the Japanese Pure Film Movement is a detailed history of Japanese cinema in the 1910s and 20s, recreating the experience of many lost films

- In 2001 the Pordenone Silent Film Festival held a Japanese silents retrospective – the detailed catalogue is available online

- Donald Richie’s much-revised A Hundred Years of Japanese Films: A Concise History, with a Selective Guide to DVDs and Videos is probably still the standard source on its subject

- Donald Richie’s 1971 classic Japanese Cinema: Film Style and National Character is freely available as an electronic publication from the University of Michigan’s Center for Japanese Studies

- More on the benshi: Jeffrey A. Dym, Benshi, Japanese Silent Film Narrators, and their Forgotten Narrative Art of Setsumei: A History of Japanese Silent Film Narration (2003)

- Da Benshi Code – various folk have a go at being a benshi for the cinema of today