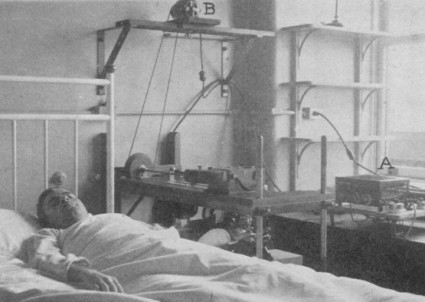

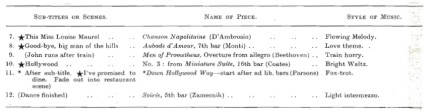

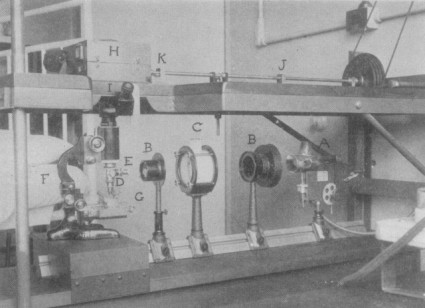

Fig 1: Photograph of the apparatus for cinematographic photomicrography of the capillaries of the nail fold in human subjects. A = an adjustable resistance; B = a motor, operated by a foot switch. From J. Hamilton Crawford and Heinz Rosenberger,’An Apparatus for Studies of Human Capillaries’, Journal of Clinical Investigation, 26 April 1926

Here at the Bioscope we like to keep an eye on online resources for the study of silent cinema, in particular digitised journals and newspapers. Few such resources exist online which are dedicated solely towards silent film, but there are plenty of a general or of a specialism other than film which contain material of great value to us. Plenty has been written here about newspapers, which you would expect to have worthwhile material, but our subject now is something a little more off the beaten track – medical journals.

It could be argued – in fact it has been argued – that it was scientific and medical investigation that brought about the invention of cinema. Chronophotographers in the 1880s and 90s, such as Etienne-Jules Marey, Georges Demeny, Ernst Kohlrausch and Albert Londe, used the emerging technology of motion picture film to record and analyse movement (chiefly human movement), generally with a medical or therapeutic aim in view. When motion pictures properly appeared on the scene, although they flourished as an entertainment, there were a number of medical investigators who took advantage of the new technology, such as Eugène-Louis Doyen (who filmed his operations in the late 1890s/early1900s) and Jean Comandon, who used microcinematographic film in completing his 1909 doctoral thesis De l’usage clinique de l’ultra-microscope en particulier pour la recherche et l’étude des spirochètes, and who went on to make films for Pathé. Other early explorers with a camera on the science/medicine border included Lucien Bull, Pierre Noguès, Gheorge Marinescu, Alejandro Posadas, Osvaldo Polimanti and Joachim-Léon Carvallo.

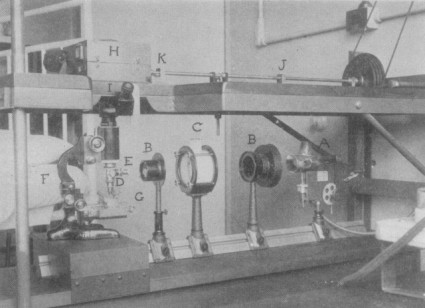

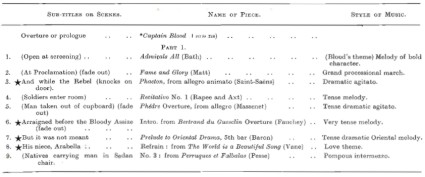

Fig. 2: Photograph showing details of the apparatus for cinematography of the capillaries. A = arc lamp; B = condensing system; C = heat filter; D = system for direct illumination; E = polarizer; F = microscope; G = stand for finger; H = camera; I = observation side piece; J = shaft; K = clutch

So it may not come as a surprise to find the cinematograph included among medical papers of the period, though the extent to which it is, and the number of people engaged in using motion pictures for medical investigation throughout the silent period, is nevertheless remarkable. Evidence of this can be found in digitised medical journals of the period, of which the major source is PubMed Central, the U.S. National Institutes of Health free digital archive of biomedical and life sciences journal literature. PMC is a digital library for a worldwide scientific and biomedical community, dedicated to the preservation and free access. It began operating in 2000, and in 2007 a UK offshoot, UK PubMed Central was launched. What is of interest to us is that its archive includes many runs of historical journals, covering (for our purposes) the 1890s to the 1920s, among them the British Medical Journal, The Journal of Medical Research, The Proceedings of the Royal Society of Medicine etc.

And there is plenty to discover. Just type in ‘cinematograph’ or ‘kinematograph’ (the most productive terms) and you will uncover a world of pioneering investigation. There is a 1918 article ‘Cinematograph Demonstration of War Neuroses’, on the renowned film of shell shock victims at Netley (previously covered by the Bioscope here), ‘The Rôle of the Cinematograph in the Teaching of Obstetrics’ (1920), ‘Kinematograph Film illustrating Anastomosis of Facial Nerve in Cases of Facial Palsy’ (1925), ‘The Cinematograph in Medical Education’ (1928) and ‘Cinematograph Demonstration of Methods of Bone-grafting’ (116). There is a number of pieces on the question whether going to the cinema was bad for your eyesight. There are references to key investigators such as Marey, Comandon, Marinescu and Doyen. And there are incidental references that intrigue, such as the British Medical Journal noting with some interest its receipt of a booklet on Kinemacolor (“With the motion of the picture and the natural colour representation, together with a certain amount of stereoscopic relief, all rolled into one, it is difficult to see what further conquests in this direction realism has to make”).

Fig. 3: Print of part of a cinematographic film taken by the method described

All of the documents are available in word-searchable PDF format, immaculately ordered and referenced, as one would expect. One can also find articles and reviews from more recent times that cover our area. Of course, the number of film enthusiasts keen to read a paper entiteld ‘An Apparatus for Motion Photography of the Growth of Bacteria’ is likely to be outnumbered to some considerable degree by those who would rather seek their entertainment elsewhere. But for those of an enquiring mind, PMC is an absolute treasure trove for anyone keen to explore how the motion picture developed in its earliest years as a tool of discovery, and gives evidence that the medical community was, from the outset, welcoming of the new medium where it could advance understanding.

There are other such medical journal databases. The British Medical Journal has puts its whole archive online, searchable by year or by subject terms. It appears that the content is the same as that to be found on PMC, but one should never assume. Next, there is the archive of historical nursing journals made available by the Royal College of Nursing. This does have material which is not on PMC, and the terms ‘cinematograph’, ‘kinematograph’ and even ‘kinetoscope’ all yield interesting results. Here, for example, is an account from The British Journal of Nursing, 15 November 1919, on a screening of the film The End of the Road:

By the courteous invitation of the National Council for Combating Venereal Diseases (London and Home Counties Branch), we attended a private exhibition of an Educational Cinematograph Production. bearing the above title. This powerful film is authorised by the Council, and produced With the approval of the Ministry of Health at the Alhambra Theatre, It is scarcely necessary to state that the splendid endeavours of the N.C.C.V.D. are bearing abundant fruit. Only a few years ago the production of a play handling social and sex questions with such frankness would not have been possible on our English stage. To-day a mixed audience watches it with the reverent silence of a Church congregation, a proof that the senseless prudery which has been so largely responsible in the past for an enormous amount of preventable disease, misery and degradation is breaking down, and giving place to a more sane, enlightened, and wholesome attitude of mind.

In the case of both the BMJ archive and that of the RCN, the article are available for free, as word-searchable and downloadable PDFs.

The history of early medical film can be traced in Virgilio Tosi’s Cinema Before Cinema: The Origins of Scientific Cinematography (first published in Italian 1984 and in English in 2005) which is accompanied by a DVD, The Origins of Scientific Cinematography, which demonstrates the work of chronophotographers, ethnographers, scientists and doctors who used film at the turn of the last century. The DVD contains some beautiful and occasionally eye-popping images (my favourite is a German doctor, Ernst von Bergmann, from 1903, who swiftly amputates a leg and then makes a bow to the camera).

Other studies around this area include Marta Braun, Picturing Time: Work of Etienne-Jules Marey (1830-1904) (one of the most beautiful books I know, as well as brimming over with intelligence) and Lisa Cartwright, Screening the Body: Tracing Medicine’s Visual Culture, a thought-provoking study of the meaning and intentions of the medical film, boldly arguing for its alliance with the avant garde and popular culture. Not published yet, but allied to Cartwright’s preoccupations, will be Hannah Landecker’s book which has the working title Cellular Features: A History of Biological Film in Science and Culture, information on which can be found here. As Landecker notes, while many medical films were shown only to specialists, or were used for instructional purposes, others made it into the popular cinema – notably the films of Jean Comandon.

One of the interesting things is that people didn’t draw the line between science and entertainment … It was all seen as film — something new. People were really excited that they could see something they’d never seen before — films of far-away places and of small things inside the body.

Has that line been drawn since? Dr Doyen’s 1902 film of the separation of Siamese twins ended up being shown on fairgrounds (and can be found on YouTube, if you know where to look), and only last month Channel 4 gave us The Operation: Surgery Live. Medical film is popular film, because we are drawn to watch it. It is certainly a part of film history that it would be wrong to ignore.