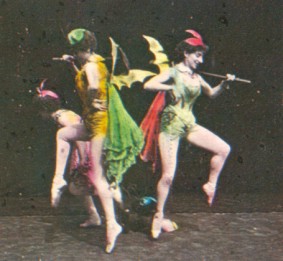

Unidentified Kinemacolor film of New York harbour (synthesised colour image)

We return, after something of a break, to our series on the history of colour cinematography in the silent era. We’re still not done with the history of Kinemacolor, the dominant natural colour process before the First World War, and there will be posts on Kinemacolor in America, Britain, and in other countries, then a post on Kinemacolor’s unhappy demise, before we move onto other colour systems.

Kinemacolor was first exhibited in America at Madison Square Gardens on 11 December 1909. 1,200 members of the film trade and general press gathered to hear George Albert Smith and Charles Urban explain their system and show twenty Kinemacolor subjects, including a film taken by John Mackenzie calculated to inspire the audience, which showed 20,000 schoolchildren forming the American flag. The intention was to find a buyer for the American rights. Urban tried to do a deal with the Motion Picture Patents Company, the monopolistic organisation which had been established in January 1909 to licence film production, distribution and exhibition exclusively, through control of the patents of Edison and others, but he failed to do so. His business timing was unfortunate, both because the MPPC was striving earnestly to stifle all independent film activity in America, and because the special equipment required for Kinemacolor ran counter to its wish to standardise the American film industry.

Children Forming United States Flag at Albany Capitol, from the 1912 Kinemacolor catalogue (note that this is an ordinary colour illustration, not a Kinemacolor ‘print’ – it was impossible to reproduce Kinemacolor as a still image).

Urban returned home disappointed, but he was pursued by two businessmen from Allentown, Pennsylvania, Gilbert Henry Aymar and James Klein Bowen. They secured the patent rights for $200,000 (£40,000), with a plan to exhibit Kinemacolor through a system of local licences in variety theatres rather than picture houses. They established the Kinemacolor Company of America in April 1910, planning not to produce their own films (at least initially), instead relying on showing British product. The business was badly mishandled, and eventually a New York stock speculator, George H. Burr & Co., paid $200,000 for the patent rights and floated a new Kinemacolor Company of America. The resultant company with patent rights was then sold in April 1911 to John J. Murdock, a theatre magnate.

Kinemacolor enjoyed a good year in 1911 owing to a succession of British royal events (including the coronation of King George V) which looked spectacular in colour. Audiences flocked to Kinemacolor theatres, happy to pay higher prices for a classy product and generally making the film industry marvel at the high tone of the proceedings and the money rolling in. But an American business could only go so far showing long newsfilms of British royalty. The Kinemacolor Company of America wanted to show fiction films. The British fiction films were uniformly terrible – so they needed to produce their own.

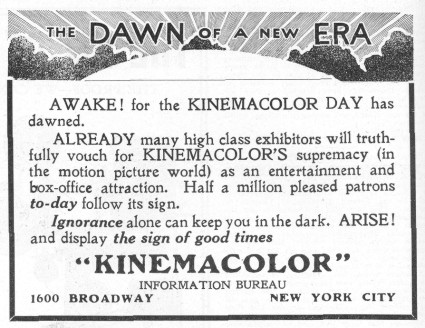

1913 Motion Picture News advert for Kinemacolor

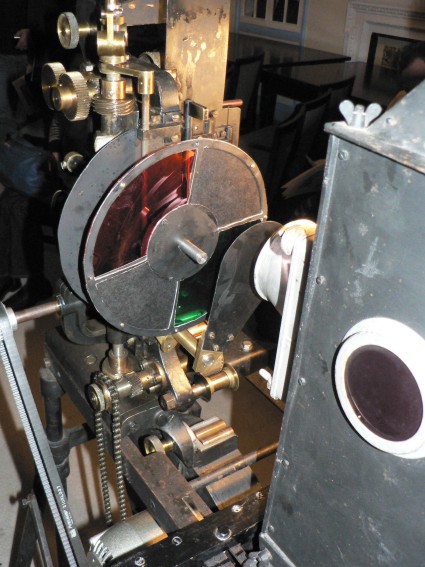

A big problem with Kinemacolor was that it was an additive system. Essentially this means that it composed its colour record by the addition of separate colour records (television works on the same principle), but in doing so it absorbed a lot of the available light. The result was that it was not a good idea to shoot Kinemacolor in the studio; you had to film in good natural light (many of the British films were not filmed in Britain but in Nice, France).

So, technically, the odds were stacked against them when they set out to produce their first film. In a bout of wild over-ambition, they choose to produce The Clansman, based on a dramatised version of Thomas Dixon’s grotesquely racist novel about the Ku Klux Klan. A deal was signed with the Southern Amusement Company, producers of The Clansman play, and the perfomers were to be from the Campbell MacCullough Players, one of the several stock companies which were touring the States with the production. The director was William Haddock. Filmed throughout 1911 in the New Orleans area, as the stock company went on the road with the play, the ten-reel film (Kinemacolor films were double the length of standard films owing to the altenating red-green records) was completed in January 1912 at a cost of $25,000.

Then what? No one is sure. One suggestion is that there were problems over the story rights, though one can hardly believe that they would film for an entire year without being sure that they had full permission from Dixon to do so. The other argument is that the film was technically inept and unshowable, but again you’d have thought someone might have spotted this over the course of the year. Whatever the reason, it was never shown publicly. Film trade journalist Frank Woods, who had contributed to the script of The Clansman, showed what he’d written to one D.W. Griffith, who then went off and filmed The Birth of a Nation, based on the same novel. Had the Kinemacolor version been exhibited, Griffith would presumably never have made his film, and film history might have been completely different.

A new head of the Kinemacolor Company of America, Henry J. Brock, took over late in 1912, and studios were established at 4500 Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood. Its first film, after the debacle of The Clansman, was a two-reeler Western, East and West (1912). But production and exhibition continued to be beset by technical problems, and too few films were produced to sustain the company, despite it eventually obtaining a licence from the Motion Picture Patents Company in August 1913, making it the only new company to join the trust after its original formation. Exhibitors in particular resisted including Kinemacolor films requiring separate projection facilities within their programmes. The Hollywood studio closed in June 1913, taken over by the D.W. Griffith company, which renamed it the Fine Arts studio, where The Birth of a Nation would be filmed. The Kinemacolor Company of America opened a studio in New York in October 1913, but gradually faded from view. It ceased production in 1915.

The lesson from the Kinemacolor Company of America was that colour alone was not enough. Karl Brown, who worked for Kinemacolor processing negatives, noted the audience reaction:

Our little one-reel pictures were made to exploit color for color’s sake. There was one about a hospital fire, showing lots of flames; another, from a Hawthorne story about a pumpkin that becomes a man, showed up the golden yellow of the carved jack-o’-lantern very well indeed. There was another about British soldiers, featuring the red and gold and white of their uniforms.

The audiences at the California seemed to care nothing about our beautiful colors. What they wanted was raw melodrama and lots of it, and what seemed to stir them most of all was the steady flood pictures made by a man named D.W. Griffith…

That man again. Brown noticed the way things were going and left to join Griffith as assistant to his cinematographer, Billy Bitzer.

Lillian Russell in what may be a frame still from Kinemacolor film of her (I can’t remember where the image comes from). As with other ‘colour’ images of Kinemacolor, the colour is not true Kinemacolor – in this case, it seems to be a still taken from a colour print approximating the colour effect.

The Kinemacolor Company of America produced both non-fiction and fiction. Among the former, its most spectacular production was The Making of the Panama Canal (1912), a nine-reeler, lasting around two hours, which enjoyed a considerable reputation in its time. Dramatic production was headed by David Miles, with directors including William Haddock, Gaston Bell, Jack Le Saint and Frank Woods; members of the stock company included Linda Arvidson Griffith (Mrs D.W. Griffith), Mabel Van Buren, Murdock MacQuarrie, Clara Bracy and Charles Perley, while theatre great Lillian Russell made a short film with Kinemacolor, entitled How to Live 100 Years, which she included in a touring show of hers promoting physical fitness. The cameramen (the real stars of the show) included John Mackenzie, Alfred Gosden, Victor Scheurich and Harold Sintzenich.

A demonstration reel from DeBergerac Productions showing how the effect of Kinemacolor can be achieved synthetically, using Kinemacolor film shot in Atlantic City and New York, c. 1913, plus what looks like a dance scene from an unidentified drama.

Few Kinemacolor Company of America films survive (few Kinemacolor films of any kind survive, full stop). One reel of three of The Scarlet Letter (1913), based on the Nathaniel Hawthorne story and starring Linda Arvidson Griffith is held by George Eastman House. The Library of Congress has two examples of ‘Mike and Meyer’ comedies from 1915 starring the famous vaudeville team of Lew Fields and Joe Weber, produced by a subsidiary company, the Weber-Fields-Kinemacolor Company. The UCLA Film and Television Archive has a few seconds of Lillian Russell, presumably from How to Live 100 Years. A handful of actualities also survive – a few frames showing President William Howard Taft, scenes of passers-by in Atlantic City and New York (see above). The rest – and we have no clear idea of the extent of the Kinemacolor Company of America’s production – is gone.

Further reading:

Eileen Bowser, The Transformation of Cinema: 1907-1915 (1990)

Karl Brown, Adventures with D.W. Griffith (1973)