Part one

Prakash Travelling Cinema is a delightful short film, posted on YouTube by the filmmaker, Megha B. Lakhani. She made the 14-minute film while at the National Institute of Design, India, and it has gone on to win festival awards.

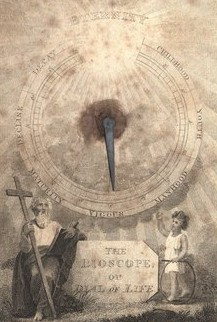

The film documents two friends who maintain a travelling bioscope show on the streets of Ahmedabad. The ramshackle outfit, which they take around on a hand-cart, comprises a genuine c.1910 Pathé projector, adapted for sound, with peep-holes all around the mobile ‘cinema’ itself (which they call their ‘lorry’), through which children watch snippets plucked from popular Bollywood titles. One of the amazing sights of the film is either of the two men hand-cranking their sound projector at exhausting speed.

Part two

Although they are not showing silent films, the whole enterprise is imbued with the spirit of the original travelling bioscope operators of India, and of course the technology hails from the silent period. The word ‘bioscope’ still persists in places in India for cinema, as it does in South Africa. However, the film wants to do more than show a quaint operation, and it is very much about friendship, conviction, Indian society, and the persistence of a human way of doing things in the face of modern media technologies.

There are an estimated 2,000 mobile cinema shows in India today, and the travelling bioscope has been made the subject of other recent films. There is Andrej Fidyk’s 1998 documentary film Battu’s Bioscope, on a modern travelling show in rural India; Vrinda Kapoor and Nitesh Bhatia’s short film Baarah Mann Ki Dhoban (2007), on modern bioscope workers whch also touches on the history of India film exhibition; and Tim Sternberg’s film Salim Baba (2007), again about a modern travelling bioscope show, this time with an adapted 1897 Bioscope. Plus there’s Tabish Khair’s acclaimed novel Filming, published this year, which moves from a travelling bioscope show in 1929 to the Bombay cinema of the 1940s as a means to examine the rise of modern India. Clearly there’s a metaphor in the air.

Prakash Travelling Cinema was made in 2006, and there’s a full set of credits here. The film is in Hindi, with English subtitles, and on YouTube, owing to its length, it comes in two parts.