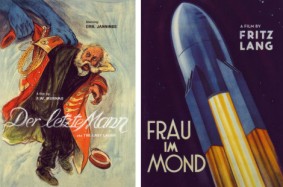

Eureka Entertainment has announced the UK release of two DVDs, F.W. Murnau’s Der letzte Mann (The Last Laugh) and Fritz Lang’s Frau im mond (Woman in the Moon). Both titles will become available on 21 January 2008. Below is some blurb from Eureka for each of the titles:

Der Letzte Mann (1924)

A landmark work in the history of the cinema, Der letzte Mann represents a breakthrough on a number of fronts. Firstly, it introduced a method of purely visual storytelling in which all intertitles and dialogue were jettisoned, setting the stage for a seamless interaction between film-world and viewer. Secondly, it put to use a panoply of technical innovations that continue to point distinct ways forward for cinematic expression nearly a century later. It guides the silent cinema’s melodramatic brio to its lowest abject abyss — before disposing of the tragic arc altogether. The lesson in all this? That a film can be anything it wants to be… but only Der letzte Mann (and a few unforgettable others) were lucky enough to issue forth into the world under the brilliant command of master director F.W. Murnau.

His film depicts the tale of an elderly hotel doorman (played by the inimitable Emil Jannings) whose superiors have come to deem his station as transitory as the revolving doors through which he has ushered guests in and out, day upon day, decade after decade. Reduced to polishing tiles beneath a sink in the gents’ lavatory and towelling the hands of Berlin’s most-vulgar barons, the doorman soon uncovers the ironical underside of old-world hospitality. And then — one day — his fate suddenly changes…

Der letzte Mann (also known as The Last Laugh, although its original title translates to “The Last Man”) inaugurated a new era of mobile camera expression whose handheld aesthetic and sheer plastic fervour predated the various “New Wave” movements of the 1960s and beyond. As the watershed entry in Murnau’s work, its influence can be detected in such later masterpieces as Faust, Sunrise, and Tabu — and in the films of the same Hollywood dream-factory that would offer him a contract shortly after Der letzte Mann‘s release. The Masters of Cinema Series is proud to present the original German domestic version of the work that some consider the greatest silent film ever made.

SPECIAL FEATURES

- New, progressive encode of the recent, magnificent film restoration

- Der letzte Mann – The Making Of – documentary by Murnau expert Luciano Berriatúa [41:00]

- New and improved optional English subtitles (original German intertitles)

- Lavishly illustrated 36-page booklet with writing by film scholars R. Dixon Smith, Tony Rayns, and Lotte H. Eisner — and more!!!

Frau im mond (1929)

Frau im Mond is: (a) The first feature-length film to portray space-exploration in a serious manner, paying close attention to the science involved in launching a vessel from the surface of the earth to the valleys of the moon. (b) A tri-polar potboiler of a picture that manages to combine espionage tale, serial melodrama, and comic-book sci-fi into a storyline that is by turns delirious, hushed, and deranged. (c) A movie so rife with narrative contradiction and visual ingenuity that it could only be the work of one filmmaker: Fritz Lang.

In this, Lang’s final silent epic, the legendary filmmaker spins a tale involving a wicked cartel of spies who co-opt an experimental mission to the moon in the hope of plundering the satellite’s vast (and highly theoretical) stores of gold. When the crew, helmed by Willy Fritsch and Gerda Maurus (both of whom had previously starred in Lang’s Spione), finally reach their impossible destination, they find themselves stranded in a lunar labyrinth without walls — where emotions run scattershot, and the new goal becomes survival.

A modern Daedalus tale which uncannily foretold Germany’s wartime push into rocket-science, Frau im Mond is as much a warning-sign against human hubris as it is a hopeful depiction of mankind’s potential. The Masters of Cinema Series is proud to present for the first time in the UK the culmination of Fritz Lang’s silent cinema, newly restored to its near-original length.

SPECIAL FEATURES

- Brand new film restoration by F. W. Murnau-Stiftung

- Original German intertitles with newly-translated optional English subtitles

- 36-page booklet which includes a newly revised analysis by Michael E. Grost on the film, and on Fritz Lang’s body of work as a whole — and more!